Shizu Saldamando, La Serena (2015). Oil, mixed media on wood panel.

La Serena, a beautiful portrait of Serena Williams by Los Angeles artist Shizu Saldamano, is currently on view at New Image Art in Santa Monica, CA, as a part of the group exhibition “The Thrill of Victory The Agony of Defeat: Sports in Contemporary Art.” Curated by Patrick Martinez, this exhibition also features work by Martinez, Gregory Bojorquez, Hiro Kurata, Mark Mulroney, Andrew Schoultz, Vincent Valdez, and Mario Ybarra Jr. I recommend seeing the show: all of these artists make very interesting work.

Saldamando, the only woman artist in this group exhibition, is (I understand) the only artist to take on the female athlete as a subject (I haven’t seen the show yet). The marginalization of women’s sports, as I’ve argued elsewhere, mirrors the wildly disproportionate scale of men’s sports as the subject of media broadcast and attention.* This goes to some of the things that make Saldamando’s work particularly interesting.

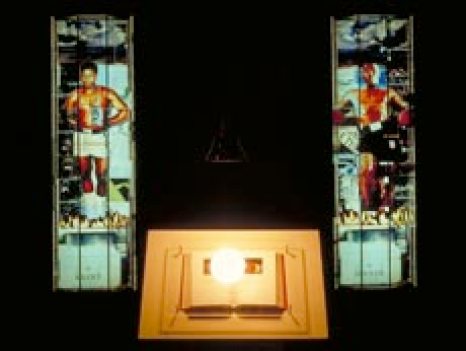

First, Serena Williams is a kind-of exception to the rule I described above. She is one of very few athletes to transcend the awfulness of mass media’s active suppression of public awareness of women athletes. The attention of a racist and sexist media, however, has mixed effects for black women athletes. The Williams sisters have been very savvy (and circumspect) in their navigation of that world, which exalts them and then tears them apart. That lifting and crushing is, of course, how mass media attention works. But the media’s wheel of fortune turns on a racist and sexist axis. Many portraits of iconic black athletes take this up, directly or indirectly. Consider, for example Keith Piper‘s installation Transgressive Acts: A Saint Among Sinners/A Sinner Among Saints (1993-1994), a twinned portrait of Muhammed Ali and Mike Tyson. They are honored, here, in the style of stained glass windows in a chapel, on whose pulpit is a copy of Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man.

In La Serena, Saldamando gives us a deliberately iconic image—the use of gold, for example, marks this work as hagiography. Serena is not just victorious, she is exalted. The portrait vibrates with the weird story of Serena Williams’s recent upset, however. This year, in the semi-finals of the US Open, a completely unspectacular player, Roberta Vinci, brought Williams’s supposedly inevitable Grand Slam triumph to a brutal stop. In advance of this tournament, the press was unrelenting in its presentation of Williams’s triumph as a certainty. This, of course, feeds the media economy which needs saints to burn at the stake.

La Serena’s gesture, at least for me, expresses an awareness of the athlete’s future struggle. La Serena’s composure — her calm, her strength, her power and defiance — might easily have been lifted from communist or labor movement works celebrating women workers (see below). It is, however, also a citation of the most famous sport spectacle of them all — Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s protest from the medal stands at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. This image belongs to a pool of images of defiance — portraits of resistance, defiance and protest.

In this photograph, one of most famous and powerful images in sports history, Smith and Carlos’s hands are raised straight up, and their heads are bowed.** In Saldamando’s portrait, Serena is looking forward, toward a future that she creates. She raises her fist, but she also flexes her muscles. The artist maximizes our access to her physical power, and the metaphysical meaning of that power. La Serena contributes to an archive of images celebrating women’s power — these images differently engage and resist the ideologies of race, sex and gender that circumscribe women’s access to her own body. Some images (Norman Rockwell’s, for example, pictured below) render the working woman’s muscular body into something folksy and hypermasculine; others feminize the woman flexing her muscles (making her muscles disappear) — how and why embodied strength appears in these images is complicated. Michelle Obama’s arms, Dyana Nyad’s (captured below in a portrait by Catherine Opie), Serena Williams’s — each appearance of a woman’s muscular strength reaches from the image into the world to shake things up.

Black women, in particular, find their bodies read through a vicious matrix that pathologizes any sign of power and defiance. Her blackness appears, within racist ideology, as a disruption of gender. This form of racism flourishes around the figures of women like the Williams sisters — by which I mean black women who are among the very best women athletes alive. Their success as athletes becomes a sign of their always-already failure as women. Thus the social media trash-heap is sprinkled with videos, blog-posts that argue that Serena Williams is, in fact, actually man [I refuse to link that racist/sexist garbage]. In that world, her arms are stolen by a frightening army of fascist lunatics who see them as evidence that she isn’t, really, even human.

Saldamando’s La Serena calmly turns that shit into gold.

*Most group exhibitions centered on sports don’t feature any works centered on women athletes. So kudos to Martinez for including Saldamando’s portraits of Serena Williams and Kristi Yamaguchi.

**Note: Peter Norman [left] was an ally in this gesture. He is wearing a pin supporting the Olympic Project for Human Rights and willingly absorbed the controversy surrounding his participation this moment.